3

Revolution suspends habit as well as law. But just as nature abhors a vacuum, people abhor anarchy.

So habits made their first incursions into the new terrain, like bacteria into rock, followed by procedures, protocols, a whole fell-field of social discourse, on its way to the climax forest of law. . . . Nadia saw that people (some people) were indeed coming to her to resolve arguments, deferring to her judgment. She might not have been in control, but she was as close to control as they had: the universal solvent, as Art called her, or General Nadia, as Maya said nastily over the wrist. Which only made Nadia shudder, as Maya knew it would. Nadia preferred something she had heard Sax say over the wrist to his faithful gang of techs, all young Saxes in the making: “Nadia is the designated arbitrator, talk to her about it.” Thus the power of names; arbitrator rather than general. In charge of negotiating what Art was calling the “phase change.” She had heard him use the term in the midst of a long interview on Mangalavid, with that deadpan expression of his that made it very hard to tell if he was joking or not: “Oh I don’t think it’s really a revolution we’re seeing, no. It’s a perfectly natural next step here, so it’s more a kind of evolutionary or developmental thing, or what in physics they call a phase change.”

His subsequent comments indicated to Nadia that he did not in fact know what a phase change was. But she did, and she found the concept intriguing. Vaporization of Terran authority, condensation of local power, the thaw finally come . . . however you wanted to think about it. Melting occurred when the thermal energy of particles was great enough to overcome the intracrystalline forces that held them in position. So if you considered the metanat order as the crystalline structure. . . . But then it made a huge difference whether the forces holding it together were interionic or intermolecular; sodium chloride, interionic, melted at 801C; methane, intermolecular, at—183°. What kind of forces, then? And how high the temperature?

At this point the analogy itself melted. But names were powerful in the human mind, no doubt about it. Phase change, integrated pest management, selective disemployment; she preferred them all to the old deadly notion revolution, and she was glad they were all in circulation, on Mangalavid and on the streets.

But there were some five thousand heavily armed security troops in Burroughs and Sheffield, she reminded herself, who were still thinking of themselves as police facing armed rioters. And that would have to be dealt with by more than semantics.

For the most part, however, things were going better than she had hoped. It was a matter of demographics, in a way; it appeared that almost every single person who had been born on Mars was now in the streets, or occupying city offices, train stations, space-ports— all of them, to judge by the Mangalavid interviews, completely (and unrealistically, Nadia thought) intolerant of the idea that powers on another planet should control them in any way whatsoever. That was nearly half the current Martian population, right there. And a good percentage of the old-timers were on their side too, as well as some of the new emigrants. “Call them immigrants,” Art advised over the phone. “Or newcomers. Call them settlers or colonialists, depending on whether they’re with us or not. That’s something Nirgal has been doing, and I think it helps people to think about things.”

On Earth the situation was less clear. The Subarashii metanats were still struggling with the southern metanats, but in the context of the great flood they had become a bitter sideshow. It was hard to tell what Terrans in general thought of the conflict on Mars.

Whatever they thought, a fast shuttle was about to arrive, with reinforcements for security. So resistance groups from all over mobilized to converge on Burroughs. Art did what he could to help this effort from inside Burroughs, locating all the people who had independently thought of coming (it was obvious, after all), telling them their idea was good, and siccing them on people opposed to the plan. He was, Nadia thought, a subtle diplomat— big, mild, unpretentious, unassuming, sympathetic, “undiplomatic”— head lowered as he conferred with people, giving them the impression they were the ones driving the process. Indefatigable, really. And very clever. Soon he had a great number of groups coming, including the Reds and the Marsfirst guerrillas, who still appeared to be thinking of their approach as a kind of assault, or siege. Nadia felt acutely that while the Reds and Marsfirsters she knew— Ivana, Gene, Raul, Kasei— were keeping in touch with her, and agreeing to the use of her as an arbitrator, there were more radical Red and Marsfirst units out there for whom she was irrelevant, or even an obstruction. This made her angry, because she was sure that if Ann was fully supporting her, the more radical elements would come around. She complained bitterly about this to Art, after seeing a Red communiqué arranging the western half of the “convergence” on Burroughs, and Art went to work and got Ann to answer a call, then gave her over in a link to Nadia.

And there she was again, like one of the furies of the French Revolution, as bleak and grim as ever. Their last exchange, over Sabishii, lay heavy between them; the issue had become moot when UNTA retook Sabishii and burned it down, but Ann was obviously still angry, which Nadia found irritating.

Brittle greetings over, their conversation degenerated almost instantly into argument. Ann clearly saw the revolt as a chance to wreck all terraforming efforts and to remove as many cities and people as possible from the planet, by direct assault if necessary. Frightened by this apocalyptic vision, Nadia argued with her bitterly, then furiously. But Ann had gone off into a world of her own. “I’d be just as happy if Burroughs did get wrecked,” she declared coldly.

Nadia gritted her teeth. “If you wreck Burroughs you wreck everything. Where are the people inside supposed to go? You’ll be no better than a murderer, a mass murderer. Simon would be ashamed.”

Ann scowled. “Power corrupts, I see. Put Sax on, will you? I’m tired of this hysteria.”

Nadia switched the call to Sax and walked away. It was not power that corrupted people, but fools who corrupted power. Well, it could be that she had been too quick to anger, too harsh. But she was frightened of that dark place inside Ann, the part that might do anything; and fear corrupted more than power. Combine the two. . . .

Hopefully she had shocked Ann severely enough to squeeze that dark place back into its corner. Bad psychology, as Michel pointed out gently, when Nadia called him in Burroughs to talk about it. A strategy resulting from fear. But she couldn’t help it, she was afraid. Revolution meant shattering one structure and creating another one, but shattering was easier than creating, and so the two parts of the act were not necessarily fated to be equally successful. In that sense, building a revolution was like building an arch; until both columns were there, and the keystone in place, practically any disruption could bring the whole thing crashing down.

• • •

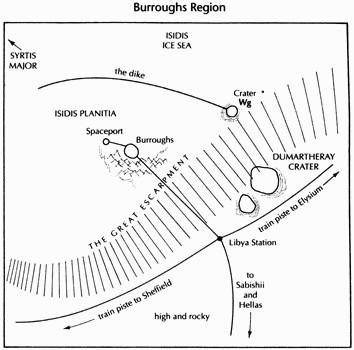

So on Wednesday evening, five days after Nadia’s call from Sax, about a hundred people left for Burroughs in planes, as the pistes were judged too vulnerable to sabotage. They flew overnight to a rocky landing strip next to a large Bogdanovist refuge in the wall of Du Martheray Crater, which was on the Great Escarpment southeast of Burroughs. They landed at dawn, with the sun rising through mist like a blob of mercury, lighting distant ragged white hills to the north, on the low plain of Isidis: another new ice sea, whose progress south had been stopped only by the arcing line of the dike, curving across the land like a long low earthen dam— which was just what it was.

To get a better view Nadia went up to the top floor of the Du Martheray refuge, where an observation window, disguised as a horizontal crack just under the rim, gave a view down the Great Escarpment to the new dike and the ice pressing against it. For a long time she stared down at the sight, sipping coffee mixed with a dose of kava. To the north was the ice sea, with its clustered seracs and long pressure ridges, and the flat white sheets of giant frozen-topped melt lakes. Directly below her lay the first low hills of the Great Escarpment, dotted with spiky expanses of Acheron cacti, sprawling over the rock like coral reefs. Staircased meadows of black-green tundra moss followed the courses of small frozen streams dropping down the Escarpment; the streams in the distance looked like long algae diatoms, tucked into creases in the redrock.

Burroughs Region

And then in the middle distance, dividing desert from ice, ran the new dike, like a raw brown scar, suturing two separate realities together.

Nadia spent a long time studying it through binoculars. Its southern end was a regolith mound, running up the apron of Crater Wg and ending right at Wg’s rim, which was about half a kilometer above the datum, well above the expected sea level. The dike ran northwest from Wg, and from her prospect high on the Escarpment Nadia could see about forty kilometers of it before it disappeared over the horizon, just to the west of Crater Xh. Xh was surrounded by ice almost to its rim, so that its round interior was like an odd red sinkhole. Everywhere else the ice had pressed right up against the dike, for as far as Nadia could see. The desert side of the dike appeared to be some two hundred meters high, although it was difficult to judge, as there was a broad trench underneath the dike. On the other side, the ice bulked quite high, halfway up or more.

The dike was about three hundred meters wide at the top. That much displaced regolith— Nadia whistled respectfully— represented several years of work, by a very large team of robot draglines and canal-diggers. But loose regolith! It seemed to her that huge as the dike was on any human scale, it was still not much to contain an ocean of ice. And ice was the easy part— when it became liquid, the waves and currents would tear regolith away like dirt. And the ice was already melting; immense melt pods were said to lie everywhere underneath the dirty white surface, including directly against the dike, seeping into it.

“Aren’t they’re going to have to replace that whole mound with concrete?” she said to Sax, who had joined her, and was looking through his own binoculars at the sight.

“Face it,” he said. Nadia prepared herself for bad news, but he continued by saying, “Face the dike with a diamond coating. That would last fairly long. Perhaps a few million years.”

“Hmm,” Nadia said. It was probably true. There would be seepage from below, perhaps. But in any case, whatever the particulars, they would have to maintain the system in perpetuity, and with no room for error, as Burroughs was just 20 kilometers south of the dike, and some 150 meters lower than it. A strange place to end up. Nadia trained her binoculars in the direction of the city, but it lay just over her horizon, about 70 kilometers to the northwest. Of course dikes could be effective; Holland’s dikes had held for centuries, protecting millions of people and hundreds of square kilometers, right up until the recent flood— and even now those great dikes were holding, and would be broached first by flanking floods through Germany and Belgium. Certainly dikes could be effective. But it was a strange fate nevertheless.

Nadia pointed her binoculars along the ragged rock of the Great Escarpment. What looked like flowers in the distance were actually massive lumps of coral cactus. A stream looked like a staircase made of lily pads. The rough redrock slope made for a very stark, surreal, lovely landscape. . . . Nadia was pierced by an unexpected paroxysm of fear, that something might go wrong and she might suddenly be killed, prevented from witnessing any more of this world and its evolution. It could happen, a missile might burst out of the violet sky at any moment— this refuge was target practice, if some frightened battery commander out at the Burroughs spaceport learned of its presence and decided to deal with the problem preemptively. They could be dead within minutes of such a decision.

But that was life on Mars. They could be dead within minutes of any number of untoward events, as always. She dismissed the thought, and went downstairs with Sax.

• • •

She wanted to go into Burroughs and see things, to be on the scene and judge for herself: walk around and observe the citizens of the town, see what they were doing and saying. Late on Thursday she said to Sax, “Let’s go in and have a look.”

But it seemed to be impossible. “Security is heavy at all the gates,” Maya told her over the wrist. “And the trains coming in are checked at the stations very closely. Same with the subway to the spaceport. The city is closed. In effect we’re hostages.”

“We can see what’s happening on-screen,” Sax pointed out. “It doesn’t matter.”

Unhappily Nadia agreed. Shikata ga nai, apparently. But she didn’t like the situation, which seemed to her to be rapidly approaching a stalemate, at least locally. And she was intensely curious about conditions in Burroughs. “Tell me what it’s like,” she asked Maya over their phone link.

“Well, they’ve got control of the infrastructure,” Maya said. “Physical plant, gates, and so on. But there aren’t enough of them to force people to stay indoors, or go to work of course, or anything else. So they don’t seem to know what to do next.”

Nadia could understand that, as she too felt at a loss. More security forces were coming into the city every hour, on trains from tent towns they had given up on. These new arrivals joined their fellow troops, and stayed near the physical plant and the city offices, getting around in heavily armed groups, unmolested. They were housed in residential quarters in Branch Mesa, Double Decker Butte, and Black Syrtis Mesa, and their leaders were meeting more or less continuously at the UNTA headquarters in Table Mountain. But the leaders were issuing no orders.

So things were in an uneasy suspension. The Biotique and Praxis offices in Hunt Mesa were still serving as an information center for all of them, disseminating news from Earth and the rest of the Mars, spreading it through the city on bulletin boards and computer postings. These media, along with Mangalavid and other private channels, meant that everyone was well informed concerning the latest developments. On the great boulevards, and in the parks, some big crowds congregated from time to time, but more often people were scattered in scores of small groups, milling around in a kind of active paralysis, something between a general strike and a hostage crisis. Everyone was waiting to see what would happen next. People seemed in good spirits, many shops and restaurants were still open, and video interviews taped in them were friendly.

Watching them while jamming down a meal, Nadia felt an aching desire to be in there, to talk to people herself. Around ten that night, realizing she was hours from sleep, she called Maya again, and asked her if she would don vidcam glasses, and go on a walk for her around the city. Maya, just as antsy as Nadia if not more so, was happy to oblige.

• • •

Soon Maya was out of the safe house, wearing vidspecs and transmitting images of what she looked at to Nadia, who sat apprehensively in a chair before a screen, in the Du Martheray refuge common room. Sax and several others ended up looking over Nadia’s shoulders, and together they watched the bouncing image Maya got with her vidcam, and listened to her running commentary.

She walked swiftly down Great Escarpment Boulevard, toward the central valley. Once down among the cart vendors in the upper end of Canal Park, she slowed her pace, and looked around slowly to give Nadia a panning shot of the scene. People were out and about everywhere, talking in groups, enjoying a kind of festival atmosphere. Two women next to Maya struck up an animated conversation about Sheffield. A group of newcomers came right up to Maya and asked her what was going to happen next, apparently confident that she would know, “Simply because I am so old!” Maya noted with disgust when they had left. It almost made Nadia smile. But then some young people recognized Maya as herself, and came over to greet her happily. Nadia watched this encounter from Maya’s point of view, noting how starstruck the people seemed. So this is what the world looked like to Maya! No wonder she thought she was so special, with people looking at her like that, as if she were a dangerous goddess, just stepped out of a myth. . . .

It was disturbing in more senses than one. It seemed to Nadia that her old companion was in danger of being arrested by security, and she said as much over the wrist. But the view on-screen waggled from side to side as Maya shook her head. “See how there aren’t any cops in sight?” Maya said. “Security is all concentrated around the gates and the train stations, and I stay away from them. Besides, why should they bother to arrest me? In effect they have this whole city arrested.”

She tracked an armored vehicle as it drove down the grassy boulevard and passed without slowing down, as if to illustrate her point. “That’s so everyone can see the guns,” Maya said darkly.

She walked down to Canal Park, then turned around and went up the path toward Table Mountain. It was cold in the city that night; lights reflecting off the canal showed that the water in it was icing over. But if security had hoped to discourage crowds, it hadn’t worked; the park was crowded, and becoming more crowded all the time. People were clumped around gazebos, or cafés, or big orange heating coils; and everywhere Maya looked more people were coming down into the park. Some listened to musicians, or people speaking with the help of little shoulder amplifiers; others watched the news on their wrists, or on lectern screens. “Rally at midnight!” someone cried. “Rally in the timeslip!”

“I haven’t heard anything about this,” Maya said apprehensively. “This must be Jackie’s doing.”

She looked around so fast that the view on Nadia’s screen was dizzying. People everywhere. Sax went to another screen and called the safe house in Hunt Mesa. Art answered there, but other than him, the safe house was nearly empty. Jackie had indeed called for a mass demonstration in the timeslip, and word had gone out over all the city media. Nirgal was out there with her.

Nadia told Maya about this, and Maya cursed viciously. “It’s much too volatile for this kind of thing! Goddamn her.”

But there was nothing they could do about it now. Thousands of people were pouring down the boulevards into Canal Park and Princess Park, and when Maya looked around, tiny figures could be seen on the rims of the mesas, and crowding the walktube bridges that spanned Canal Park. “The speakers are going to be up in Princess Park,” Art said from Sax’s screen.

Nadia said to Maya: “You should get up there, Maya, and fast. You might be able to help keep the situation under control.”

Maya took off, and as she made her way through the crowd, Nadia kept talking to her, giving her suggestions for what she should say if she got a chance to speak. The words tumbled out of her, and when she paused for thought, Art passed along ideas of his own, until Maya said, “But wait, wait, is any of this true?”

“Don’t worry if it’s true,” Nadia said.

“Don’t worry if it’s true!” Maya shouted into her wristpad. “Don’t worry if what I say to a hundred thousand people, what I say to everyone on two worlds, is true or not?”

“We’ll make it true,” Nadia said. “Just give it a try.”

Maya began to run. Others were walking in the same direction as she was, up through Canal Park, toward the high ground between Ellis Butte and Table Mountain, and her camera gave them bobbing images of the backs of heads and the occasional excited face, turned to look at her as she shouted for clearance. Great roars and cheers were rippling through the crowd ahead, which became denser and denser, until Maya had to slow down, and then to shove and twist through gaps between groups. Most of these people were young, and much taller than Maya, and Nadia went to Sax’s screen to watch the Managalavid cameras’ images, which were cutting back and forth between a camera on the speakers’ platform, set on the rim of an old pingo over Princess Park, and a camera up in one of the walktube bridges. Both angles showed that the crowd was getting immense— maybe eighty thousand people, Sax guessed, his nose a centimeter from the screen, as if he were counting them individually. Art managed to link up to Maya along with Nadia, and he and Nadia continued to talk to her as she fought her way forward through the crowd.

Antar had finished a short incendiary speech in Arabic while Maya was making her final push through the crowd, and Jackie was now up on the speakers’ platform before a bank of microphones, making a speech that was amplified through big speakers on the pingo, and then reamplified by radio to auxiliary speakers placed all over Princess Park, and also to shoulder speakers, and lecterns, and wristpads, until her voice was everywhere— and yet, as every phrase echoed a bit off Table Mountain and Ellis Butte, and was welcomed by cheers, she could still only be heard part of the time. “. . . Will not allow Mars to be used as a replacement world . . . an executive ruling class who are primarily responsible for the destruction of Terra . . . rats trying to leave a sinking ship . . . make the same mess of things on Mars if we let them! . . . not going to happen! Because this is now a free Mars! Free Mars! Free Mars!”

And she punched a finger at the sky and the crowd roared the words out, louder and louder with each repetition, falling quickly into a rhythm that allowed them to shout together—”Free Mars! Free Mars! Free Mars! Free Mars!”

While the huge and still growing crowd was chanting this, Nirgal made his way up the pingo and onto the platform, and when people saw him, many of them began shouting “Nir-gal,” either in time with “Free Mars” or in the pauses between, so that it became “Free Mars (Nir-gal) Free Mars (Nir-gal),” in an enormous choral counterpoint.

When he reached the microphone, Nirgal waved a hand for quiet. The chanting, however, did not stop, but changed over entirely to “Nir-gal, Nir-gal, Nir-gal, Nir-gal,” with an enthusiasm that was palpable, vibrating in the sound of that great collective voice, as if every single person out there was one of his friends, and enormously pleased at his appearance— and, Nadia thought, he had been traveling for so much of his life that this might not be all that far from the truth.

The chanting slowly diminished, until the crowd noise was a general buzz, quite loud, above which Nirgal’s amplified greeting could be heard pretty well. As he spoke, Maya continued to make her way through the crowd toward the pingo, and as people stilled, it became easier for her. Then when Nirgal began to speak, she stopped as well and just watched him, sometimes remembering to move forward during the cheers and applause that ended many sentences.

His speaking style was low-key, calm, friendly, slow. It was easier to hear him. “For those of us born on Mars,” he said, “this is our home.”

He had to pause for most of a minute as the crowd cheered. They were mostly natives, Nadia saw again; Maya was shorter than almost everyone out there.

“Our bodies are made of atoms that until recently were part of the regolith,” Nirgal went on. “We are Martian through and through. We are living pieces of Mars. We are human beings who have made a permanent, biological commitment to this planet. It is our home. And we can never go back.” More cheers at this very well-known slogan.

“Now, as for those of us who were born on Earth— well, there are all different kinds, aren’t there. When people move to a new place, some intend to stay and make it their new home, and we call those settlers. Others come to work for a while and then go back where they came from, and those we call visitors, or colonialists.

“Now natives and settlers are natural allies. After all, natives are no more than the children of earlier settlers. This is home to all of us together. As for visitors— there is room on Mars for them too. When we say that Mars is free, we are not saying Terrans can no longer come here. Not at all! We are all children of Earth, one way or another. It is our mother world, and we are happy to help it in every way we can.”

The noise diminished, the crowd seeming somewhat surprised by this assertion.

“But the obvious fact,” Nirgal went on, “is that what happens here on Mars should not be decided by colonialists, or by anyone back on Earth.” Cheers began, drowning out some of what he said. “— A simple statement of our desire for self-determination . . . our natural right . . . the driving force of human history. We are not a colony, and we won’t be treated as one. There is no such thing as a colony anymore. We are a free Mars.”

More cheers, louder than ever, flowing into more chanting of “Free Mars! Free Mars!”

Nirgal interrupted the chanting. “What we intend to do now, as free Martians, is to welcome every Terran who wants to come to us. Whether to live here for a time and then go back, or else to settle here permanently. And we intend also to do everything we can to help Earth in its current environmental crisis. We have some expertise with flooding” (cheers) “and we can help. But this help, from now on, will no longer come mediated by metanationals, exacting their profits from the exchange. It will come as a free gift. It will benefit the people of Earth more than anything that could be extracted from us as a colony. This is true in the strict literal sense of the amount of resources and work that will be transferred from Mars to Earth. And so we hope and trust that everyone on both worlds will welcome the emergence of a free Mars.”

And he stepped back and waved a hand, and the cheering and chanting erupted again. Nirgal stood on the platform, smiling and waving, looking pleased, but somewhat at a loss concerning what to do next.

All through his speech Maya had continued to inch forward during the cheering, and now Nadia could see by her vidcam image that she was at the platform’s edge, standing in the first row of people. Her arms blocked the image again and again, and Nirgal caught sight of the waving, and looked at her.

When he saw who she was, he smiled and came right over, and helped boost her onto the platform. He led her over to the microphones, and Nadia caught a final image of a surprised and displeased Jackie Boone before Maya whipped off her vidcam spectacles. The image on Nadia’s screen swung wildly, and ended up showing the planks of the platform. Nadia cursed and hurried over to Sax’s screen, her heart in her throat.

Sax still had the Mangalavid image, now taken from the camera on the walktube arching from Ellis Butte to Table Mountain. From this angle they could see the sea of people surrounding the pingo, and filling the city’s central valley far down into Canal Park; it had to be most of the people in Burroughs, surely. On the makeshift stage Jackie appeared to be shouting into Nirgal’s ear. Nirgal did not respond to her, and in the middle of her exhortation he went up to the mikes. Maya looked small and old next to Jackie, but she was drawn up like an eagle, and when Nirgal said into the mikes, “We have Maya Toitovna,” the cheers were huge.

Maya made chopping motions as she walked forward, and said into the mikes, “Quiet! Quiet! Thank you! Thank you. Be quiet! We have some serious announcements to make here as well.”

“Jesus, Maya,” Nadia said, clutching the back of Sax’s chair.

“Mars is now independent, yes. Quiet! But as Nirgal just said, this does not mean we exist in isolation from Earth. This is impossible. We are claiming sovereignty according to international law, and we appeal to the World Court to confirm this legal status immediately. We have signed preliminary treaties affirming this independence, and establishing diplomatic relations, with Switzerland, India, and China. We have also initiated a nonexclusive economic partnership with the organization Praxis. This, like all arrangements we will make, will be not-for-profit, and designed to maximally benefit both worlds. All these treaties taken together begin the creation of our formal, legal, semiautonomous relationship with the various legal bodies of Earth. We fully expect immediate confirmation and ratification of all these agreements, by the World Court, the United Nations, and all other relevant bodies.”

Cheers followed this announcement, and though they were not as loud as they had been for Nirgal, Maya allowed them to go on. When they had died down a bit, she continued.

“As for the situation here on Mars, our intentions are to meet here in Burroughs immediately, and use the Dorsa Brevia Declaration as the starting point for the establishment of a free Martian government.”

Cheers again, much more enthusiastic. “Yes yes,” Maya said impatiently, trying to cut them off again. “Quiet! Listen! Before any of that, we must address the problem of opposition. As you know, we are meeting here in front of the headquarters of the United Nations Transitional Authority security forces, who are this very moment listening along with the rest of us, there inside Table Mountain.” She pointed. “Unless they have come out to join us.” Cheers, shouting, chanting. “. . . . I want to say to them now that we mean them no harm. It is the Transitional Authority’s job, now, to see that the transition has taken on a new form. And to order its security forces to stop trying to control us. You cannot control us!” Mad cheers. “. . . mean you no harm. And we assure you that you have free access to the spaceport, where there are planes that can take all of you to Sheffield, and from there up to Clarke, if you do not care to join us in this new endeavor. This is not a siege or a blockade. This is, simply enough—”

And she stopped, and put out both hands: and the crowd told her.

• • •

Over the sound of the chanting Nadia tried to get through to Maya, still up on the stage, but it was obviously impossible for her to hear. Finally, however, Maya looked down at her wristpad. The image trembled; her arm was shaking.

“That was great, Maya! I am so proud of you!”

“Yes, well, anyone can make up stories!”

Art said loudly, “See if you can get them to disperse!”

“Right,” Maya said.

“Talk to Nirgal,” Nadia said. “Get him and Jackie to do it. Tell them to make sure there isn’t any rush on Table Mountain, or anything like. Let them do it.”

“Ha,” Maya exclaimed. “Yes. We will let Jackie do it, won’t we.”

After that her wristpad’s little camera image swung everywhere, and the noise was too great for the linked observers to make anything out. The Mangalavid cameras showed a big clump of people onstage conferring.

Nadia went over and sat down on a chair, feeling as drained as if she had had to make the speech herself. “She was great,” she said. “She remembered everything we told her. Now we just have to make it real.”

“Just saying it makes it real,” Art said. “Hell, everyone on both worlds saw that. Praxis will be on it already. And Switzerland will surely back us. No, we’ll make it work.”

Sax said, “Transitional Authority might not agree. Here’s a message in from Zeyk. Red commandos have come down from Syrtis. They’ve taken over the western end of the dike. They’re moving east along it. They’re not that far from the spaceport.”

“That’s just what we want to avoid!” Nadia cried. “What do they think they’re doing!”

Sax shrugged.

“Security isn’t going to like that at all,” Art said.

“We should talk to them directly,” Nadia said, thinking it over. “I used to talk to Hastings when he was Mission Control. I don’t remember much about him, but I don’t think he was any kind of screaming crazy person.”

“Couldn’t hurt to find out what he’s thinking,” Art said.

• • •

So she went to a quiet room, and got on a screen, and made a call to UNTA headquarters in Table Mountain, and identified herself. Though it was now about two in the morning, she got through to Hastings in about five minutes.

She recognized him immediately, though she would have said she had long since forgotten his face. A short thin-faced harried technocrat, with a bit of a temper. When he saw her on his screen he grimaced. “You people again. We sent the wrong hundred, I’ve always said that.”

“No doubt.”

Nadia studied his face, trying to imagine what kind of man could have headed Mission Control in one century and the Transitional Authority in the next. He had been irritated with them frequently when they were on the Ares, haranguing them for every little deviation from the regulations, and getting truly furious when they temporarily stopped sending back video, late in the trip. A rules and regs bureaucrat, the kind of man Arkady had despised. But a man you could reason with.

Or so it seemed to her at first. She argued with him for ten or fifteen minutes, telling him that the demonstration he had just witnessed outside in the park was part of what had happened everywhere on Mars— that the whole planet had turned against them— that they were free to go to the spaceport and leave.

“We’re not going to leave,” Hastings said.

His UNTA forces controlled the physical plant, he told her, and therefore the city was his. The Reds might take over the dike, but there was no chance they would broach it, because there were two hundred thousand people in the city, who were in effect hostages. Expert reinforcements were due to arrive with the next continuous shuttle, which was going to make its orbital insertion in the next twenty-four hours. So the speeches meant nothing. Posturing only.

He was calm as he told Nadia this— if he hadn’t been so disgusted, Nadia might even have called him complacent. It seemed more than likely that he had orders from home, telling him to sit tight in Burroughs and wait for the reinforcements. No doubt the UNTA division in Sheffield had been told the same. And with Burroughs and Sheffield still in their hands, and reinforcements due any minute, it was not surprising they thought they had the upper hand. One might even say they were justified. “When people come to their senses,” Hasting said to her sternly, “we’ll be in control here again. The only thing that really matters now is the Antarctic flood, anyway. It’s crucial to support the Earth in its time of need.”

Nadia gave up. Hastings was clearly a stubborn man, and besides, he had a point. Several points. So she ended the conference as politely as she could, asking to get back to him later, in what she hoped was Art’s diplomatic style. Then she went back out to the others.

• • •

As the night went on, they continued to monitor reports coming in from Burroughs and elsewhere. Too much was happening to allow Nadia to feel comfortable going to bed, and apparently Sax and Steve and Marian and the other Bogdanovists in Du Martheray felt similarly. So they sat slumped in their chairs, sandy-eyed and aching as the hours passed and the images on the screen flickered. Clearly some of the Reds were detaching from the main resistance coalition, following some sort of agenda of their own, escalating their campaign of sabotage and direct assault all over the planet, taking small stations by force and then, as often as not, putting the occupants in cars, and blowing the stations up. Another “Red army” also successfully stormed the physical plant in Cairo, killing many of the security guards inside, and getting the rest to surrender.

This victory had encouraged them, but elsewhere the results were not so good; it appeared from some scattered survivors’ calls that a Red attack on the occupied physical plant in Lasswitz had destroyed it, and massively broached the tent, so that those who had not managed to get into secure buildings, or out into cars, had died. “What are they doing?” Nadia cried. But no one answered her. These groups were not returning her calls. And neither was Ann.

“I wish they would at least discuss their plans with the rest of us,” Nadia said fearfully. “We can’t let things spiral out of control, it’s too dangerous . . .”

Sax was pursing his lips, looking uneasy. They went to the commons to get some breakfast, and then some rest. Nadia had to force herself to eat. It was exactly a week since Sax’s first call, and she couldn’t recall anything she had eaten in that week. Indeed, on reflection she found she was ravenous. She began to shovel down scrambled eggs.

When they were almost done eating Sax leaned over and said, “You mentioned discussing plans.”

“What,” Nadia said, her fork stalled halfway to her face.

“Well, this incoming shuttle, with the security task force on board?”

“What about it?” After the flight over Kasei Vallis, she did not trust Sax to be rational; the fork in her hand began to tremble visibly.

He said, “Well, I have a plan. My group in Da Vinci thought of it, actually.”

Nadia tried to steady the fork. “Tell me.”

• • •

The rest of that day was a blur to Nadia, as she abandoned any attempt to rest, and tried to reach Red groups, and worked with Art drafting messages to Earth, and told Maya and Nirgal and the rest in Burroughs about Sax’s latest. It seemed that the pace of events, already accelerated, had caught gears with something spinning madly, and had now accelerated out of anyone’s control, leaving no time to eat or sleep or go to the bathroom. But all those things had to be done, and so she staggered down to the women’s room and took a long shower, then ate a spartan lunch of bread and cheese, and then stretched out on a couch and caught some sleep; but it was the kind of restless shallow sleep in which her mind continued to tick over, thinking fuzzy distorted thoughts about the events of the day, incorporating the voices there in the room with her. Nirgal and Jackie were not getting along; was this a problem for the rest of them?

Then she was up again, as exhausted as before. The people in the room were still talking about Jackie and Nirgal. Nadia went off to the bathroom, and then hunted for coffee.

Zeyk and Nazik and a large Arab contingent had arrived at Du Martheray while she was sleeping, and now Zeyk stuck his head into the kitchen: “Sax says the shuttle is about to arrive.”

Du Martheray was only six degrees north of the equator, and so they were well situated to see this particular aerobraking, which was going to happen just after sunset. The weather cooperated, and the sky was cloudless and very clear. The sun dropped, the eastern sky darkened, and the arch of colors above Syrtis to the west was a spectrum array, shading through yellow, orange, a narrow pale streak of green, teal blue, and indigo. Then the sun disappeared over the black hills, and the sky colors deepened and turned transparent, as if the dome of the sky had suddenly grown a hundred times larger.

And in the midst of this color, between the two evening stars, a third white star burst into being and shot up the sky, leaving a short straight contrail. This was the usual dramatic appearance that aerobraking continuous shuttles made as they burned into the upper atmosphere, almost as visible by day as by night. It only took about a minute for them to cross the sky from one horizon to the other, slow brilliant shooting stars.

But this time, when it was still high in the west, it got fainter and fainter, until it was no more than a faint star. And was gone.

Du Martheray’s observation room was crowded, and many exclaimed at this unprecedented sight, even though they had been warned. When it was completely gone Zeyk asked Sax to explain it for those of them who had not heard the full story. The orbital insertion window for aerobraking shuttles was narrow, Sax told them, just as it had been for the Ares back in the beginning. There was very little room for error. So Sax’s technical group in Da Vinci Crater had equipped a rocket with a payload of metal bits— like a keg of scrap iron, he said— and they had shot it off a few hours before. The payload had exploded in the approaching shuttle’s MOI path just a few minutes before its arrival, casting the metal fragments in a band that was wide horizontally but narrow vertically. Orbital insertions were completely computer-controlled, of course, and so when the shuttle’s radar had identified the patch of debris, the AI navigating the shuttle had had very few options. Diving below the debris would have put the shuttle through thicker atmosphere, very likely burning it up; going through the debris would risk holing the heat shield, likewise burning it up. Shikata ga nai, then; given the risk levels programmed into it, the AI had had to abort the aerobraking run by flying above the debris, thus skipping back out of the atmosphere. Which meant the shuttle was still moving outward in the solar system at very near its top speed of 40,000 kilometers per hour.

“Do they have any way to slow down except aerobraking?” Zeyk asked Sax.

“Not really. That’s why they aerobrake.”

“So the shuttle is doomed?”

“Not necessarily. They can use another planet as a gravity handle to swing around, and come back here, or go back to Earth.”

“So they’re on their way to Jupiter?”

“Well, Jupiter is on the other side of the solar system right now.”

Zeyk was grinning. “They’re on their way to Saturn?”

“They may be able to pass very close to several asteroids sequentially,” Sax was saying, “and redirect their crash— their course.”

Zeyk laughed, and though Sax went on about course correction strategies, too many other people were talking for anyone to be able to hear him.

• • •

So they no longer had to worry about security reinforcements from Earth, at least not immediately. But Nadia thought that this fact might make the UNTA police in Burroughs feel trapped, and thus more dangerous to them. And at the same time, the Reds were continuing to move north of the city, which no doubt added to security’s trapped feeling. On the same night as the shuttle’s flyby, groups of Reds in armored cars completed their takeover of the dike. That meant they were fairly close to the Burroughs spaceport, which was located just ten kilometers northwest of the city.

Maya appeared on-screen, looking no different than she had before her great speech. “If the Reds take the spaceport,” she said to Nadia, “security will be trapped in Burroughs.”

“I know. That’s just what we don’t want. Especially now.”

“I know. Can’t you keep those people under control?”

“They’re not consulting me anymore.”

“I thought you were the great leader here.”

“I thought it was you,” Nadia snapped back.

Maya laughed, harsh and humorless.

Another report came in from Praxis, a package of Terran news programs that had been relayed off Vesta. Most of it was the latest information on the flood, and the disasters in Indonesia and in many other coastal areas, but there was some political news as well, including some instances of nationalization of metanat holdings by the militaries of some client countries in the Southern Club, which the Praxis analysts thought might indicate the beginnings of a revolt by governments against metanats. As for the mass demonstration in Burroughs, it had made the news in many countries, and was certainly a topic in government offices and boardrooms around the world. Switzerland had confirmed that it was establishing diplomatic relations with a Martian government “to be designated later,” as Art said with a grin. Praxis had done the same. The World Court had announced that it would consider the suit brought by the Dorsa Brevia Peaceful Neutral Coalition against UNTA— a suit dubbed “Mars vs. Terra” by the Terran media— as soon as possible. And the continuous shuttle had reported its missed insertion; apparently it planned to turn around in the asteroids. But Nadia found it extremely encouraging that none of these events were being treated as first-headline news on Earth, where the chaos caused by the flooding was still paramount in everyone’s attention. There were millions of refugees everywhere, and many of them in immediate need. . . .

But this was why they had launched the revolt when they had. On Mars, the independence movements had most of the cities under their control. Sheffield was still a metanational stronghold, but Peter Clayborne was up there, in command of all the insurgents on Pavonis, coordinating their activities in a way that they had not been able to match around Burroughs. Partly this was because many of the most radical elements of the resistance had avoided Tharsis, and partly because the situation in Sheffield was extremely difficult, with little room for maneuvering. The insurgents now controlled Arsia and Ascraeus, and the little scientific station in Crater Zp on Olympus Mons; and they even had control of most of Sheffield town. But the elevator socket, and the whole quarter of the city surrounding it, were firmly in the hands of the security police, and they were heavily armed. So Peter had his hands full on Tharsis, and would not be able to help them around Burroughs. Nadia talked to him briefly, describing the situation in Burroughs and begging him to call Ann and ask her to get the Reds to show some restraint. He promised to do what he could, but did not seem confident that he had his mother’s ear.

After that Nadia tried another call to Ann, but did not get through. Then she tried to reach Hastings, and he took her call, but it was not a productive exchange. Hastings was no longer anything like the complacent disgusted figure she had talked to the night before. “This occupation of the dike!” he exclaimed angrily. “What are they trying to prove? Do you think I believe that they’ll cut the dike when there’s two hundred thousand people in this city, most of them on your side? It’s absurd! But you listen to me, there are people in this organization who don’t like the danger it puts the population in! I tell you, I can’t be responsible for what happens if those people don’t get the hell off that dike— off Isidis Planitia entirely! You get them off there!”

And he cut the connection before Nadia could even reply, distracted by someone off-screen who had come in during the middle of his tirade. A frightened man, Nadia thought, feeling the iron walnut tugging inward again. A man who no longer felt in control of the situation. An accurate assessment, no doubt. But she had not liked that last look on his face. She even tried to call back, but no one in Table Mountain would answer anymore.

• • •

A couple of hours later Sax woke her up in her chair, and she found out what Hastings had been so worried about. “The UNTA unit that burned Sabishii went out in armored cars and tried to— to take the dike away from the Reds,” Sax told her, looking grave. “Apparently there’s been a fight over the section of the dike nearest the city. And we’ve just heard from some Red units up there that the dike has been broached.”

“What?”

“Blown up. They had drilled holes and set charges to use as a— as a threat. And in the fighting they ended up setting them off. That’s what they said.”

“Oh my God.” Her drowsiness was gone in a flash, blown away in her own internal explosion, a great blast of adrenaline racing all through her. “Have you got any confirmation?”

“We can see a dustcloud blocking the stars. A big one.”

“Oh my God.” She went to the nearest screen, her heart thudding in her chest. It was three A.M. “Is there a chance ice will choke the gap, and serve as a dam?”

Sax squinted. “I don’t think so. Depends on how big the gap is.”

“Can we set counterexplosions and close the gap?”

“I don’t think so. Look, here’s video sent from some Reds south of the break on the dike.” He pointed at a screen, which displayed an IR image with black to the left and blackish green to the right, and a forest-green spill across the middle. “That’s the blast zone there in the middle, warmer than the regolith. The explosion appears to have been set next to a pod of liquid water. Or else there was an explosion set to liquefy the ice behind the break. Anyway, that’s a lot of water coming through. And that will widen the break. No, we’ve got a problem.”

“Sax,” she exclaimed, and held on to his shoulder as she stared at the screen. “The people in Burroughs, what are they supposed to do? God damn it, what could Ann be thinking?”

“It might not have been Ann.”

“Ann or any of the Reds!”

“They were attacked. It could have been an accident. Or someone on the dike must have thought they were going to get forced away from the explosives. In which case it was a use-it-or-lose-it situation.” He shook his head. “Those are always bad.”

“Damn them.” Nadia shook her head hard, trying to clear it. “We have to do something!” She thought frantically. “Are the mesa tops high enough to stay above the flood?”

“For a while. But Burroughs is at about the lowest point in that little depression. That’s why it was sited there. Because the sides of the bowl gave it long horizons. No. The mesa tops will get covered too. I can’t be sure how long it will take, because I’m not sure of the flow rate. But let’s see, the volume to be filled is about . . .” He tapped away madly, but his eyes were blank, and suddenly Nadia saw that there was another part of his mind doing the calculation faster than the AI, a gestalt envisioning of the situation, staring at infinity, shaking his head back and forth like a blind man. “It could be pretty fast,” he whispered before he was done typing. “If the melt pod is big enough.”

“We have to assume it is.”

He nodded.

They sat there beside each other, staring at Sax’s AI.

Sax said hesitantly, “When I was working in Da Vinci, I tried to think out the possible scenarios. The shapes of things to come. You know? And I worried that something like this might happen. Broken cities. Tents, I thought it would be. Or fires.”

“Yes?” Nadia said, looking at him.

“I thought of an experiment— a plan.”

“Tell me,” Nadia said evenly.

But Sax was reading what looked like a weather update, which had just appeared over the figures scrolling on his screen. Nadia patiently waited him out, and when he looked up from his AI again, she said, “Well?”

“There’s a high-pressure cell, coming down Syrtis from Xanthe. It should be here today. Tomorrow. On Isidis Planitia the air pressure will be about three hundred and forty millibars, with roughly forty-five percent nitrogen, forty percent oxygen, and fifteen percent carbon diox—”

“Sax, I don’t care about the weather!”

“It’s breathable,” he said. He eyed her with that reptile expression of his, like a lizard or a dragon, or some cold posthuman creature, fit to inhabit the vacuum. “Almost breathable. If you filter the CO2. And we can do that. We manufactured face-masks in Da Vinci. They’re made from a zirconium alloy lattice. It’s simple. CO2 molecules are bigger than oxygen or nitrogen molecules, so we made a molecular sieve filter. It’s an active filter too, in that there’s a piezoelectric layer, and the charge generated when the material bends during inhalation and exhalation— powers an active transfer of oxygen through the filter.”

“What about dust?” Nadia said.

“It’s a set of filters, graded by size. First it stops dust, then fines, then CO2.” He looked up at Nadia. “I just thought people might— need to get out of a city. So we made half a million of them. Strap the masks on. The edges are sticky polymer, they stick to skin. Then breathe the open air. Very simple.”

“So we evacuate Burroughs.”

“I don’t see any alternative. We can’t get that many people out by train or air fast enough. But we can walk.”

“But walk to where?”

“To Libya Station.”

“Sax, it’s about seventy k from Burroughs to Libya Station, isn’t it?”

“Seventy-three kilometers.”

“That’s a hell of a long way to walk!”

“I think most people could manage it if they had to,” he said. “And those who can’t could be picked up by rovers or dirigibles. Then as people get to Libya Station, they can leave by train. Or dirigible. And the station will hold maybe twenty thousand at a time. If you jam them in.”

Nadia thought about it, looking down at Sax’s expressionless face. “Where are these masks?”

“They’re back at Da Vinci. But they’re already stowed in fast planes, and we could get them here in a couple hours.”

“Are you sure they work?”

Sax nodded. “We tried them. And I brought a few along. I can show you.” He got up and went to his old black bag, opened it, pulled out a stack of white facemasks. He gave Nadia one. It was a mouth-and-nose mask, and looked very much like a conventional dust mask used in construction, only thicker, and with a rim that was sticky to the touch.

Nadia inspected it, put it over her head, tightened the thin strap. She could breathe through it as easily as through a dust mask. No sensation of obstruction at all. The seal seemed good.

“I want to try it outside,” she said.

• • •

First Sax sent word to Da Vinci to fly the masks over, and then they went down to the refuge lock. Word of the plan and the trial had gotten around, and all the masks Sax had brought were quickly spoken for. Going out along with Nadia and Sax were about ten other people, including Zeyk, and Nazik, and Spencer Jackson, who had arrived at Du Martheray about an hour before.

They all wore the current styles of surface walker, which were jumpsuits made of layered insulated fabrics, including heating filaments, but without any of the old constrictive material that had been needed in the early low-pressure years. “Try leaving your walker heaters off,” Nadia told the others. “That way we can see what the cold feels like if you’re wearing city clothes.”

They put the masks over their faces, and went into the garage lock. The air in it got very cold very fast. And then the outer door opened.

They walked out onto the surface.

It was cold. The shock of it hit Nadia in the forehead, and the eyes. It was hard not to gasp a little. Going from 500 millibars to 340 would no doubt account for that. Her eyes were running, her nose as well. She breathed out, breathed in. Her lungs ached with the cold. Her eyes were right out in the wind— that was the sensation that most struck her, the exposure of her eyes. She shivered as the cold penetrated her walker’s fabrics, and the inside of her chest. The chill had a Siberian edge to it, she thought. 260Âdeg;K,—13° Centigrade— not that bad, really. She just wasn’t used to it. Her hands and feet had gotten chilled many a time on Mars, but it had been years and years— over a century in fact!— since her head and lungs had felt the cold like this.

The others were talking loudly to each other, their voices sounding funny in the open air. No helmet intercoms! Her walker’s neckring, where the helmet ought to have rested, was extremely cold on her collarbones and the back of her neck. The ancient broken black rock of the Great Escarpment was covered with a thin night frost. She had peripheral vision such as she never had in a helmet— wind— tears running down her cheeks from the cold. She felt no particular emotion. She was surprised by how things looked unobstructed by a faceplate or any other window; they had a sharp-edged hallucinatory clarity, even in starlight. The sky in the east was a rich predawn Prussian blue, with high cirrus clouds already catching the light, like pink mares’ tails. The ragged corrugations of the Great Escarpment were gray-on-black in the starlight, lined with black shadows. The wind in her eyes!

People were talking without intercoms, their voices thin and disembodied, their mouths hidden by the masks. There was no mechanical hum, buzz, hiss, or whoosh; after over a century of such noise, the windy silence of the outdoors was strange, a kind of aural hollowness. Nazik looked like she was wearing a Bedouin veil.

“It’s cold,” she said to Nadia. “My ears are burning. I can feel the wind on my eyes. On my face.”

“How long will the filters last?” Nadia said to Sax, speaking loudly to be sure she was heard.

“A hundred hours.”

“Too bad people have to breath out through them.” That would add a lot more CO2 to the filter.

“Yes. But I couldn’t see a simple way around it.”

They were standing on the surface of Mars, bareheaded. Breathing the air with the aid of nothing more than a filter mask. The air was thin, Nadia judged, but she did not feel lightheaded. The high percentage of oxygen was making up for the low atmospheric pressure. It was the partial pressure of oxygen that counted, and so with the percentage of oxygen in the atmosphere so high. . . .

Zeyk said, “Is this is the first time anyone’s done this?”

“No,” Sax said. “We did it a lot in Da Vinci.”

“It feels good! It’s not as cold as I thought it would be!”

“And if you walk hard,” Sax said, “you’ll warm up.”

They walked around a bit, careful of their footing in the dark. It was quite cold, no matter what Zeyk said. “We should go back in,” Nadia said.

“You should stay out and see the dawn,” Sax said. “It’s nice without helmets.”

Nadia, surprised to hear such a sentiment coming from him, said, “We can see other dawns. Right now we have a lot to talk about. Besides, it’s cold.”

“It feels good,” Sax said. “Look, there’s Kerguelen cabbage. And sandwort.” He kneeled, brushed a hairy leaf aside to show them a hidden white flower, barely visible in the predawn light.

Nadia stared at him.

“Come on in,” she said.

So they went back.

• • •

They took their masks off inside the lock, and then they were back in the refuge’s changing room, rubbing their eyes and blowing into their gloved hands. “It wasn’t so cold!” “The air tasted sweet!”

Nadia pulled off her gloves and felt her nose. The flesh was chilled, but it was not the white cold of incipient frostbite. She looked at Sax, whose eyes were gleaming with a wild expression, very unlike him— a strange and somehow moving sight. They all looked excited for that matter, stuffed to the edge of laughter with a peculiar exhilaration, edged by the dangerous situation down the slope in Burroughs. “I’ve been trying to get the oxygen levels up for years,” Sax was saying to Nazik and Spencer and Steve.

Spencer said, “I thought that was to get your fire in Kasei Vallis to burn hard.”

“Oh no. As far as fire goes, once you’ve got a certain amount of oxygen, it’s more a matter of aridity and what materials there are to burn. No, this was to get the partial pressure of oxygen up, so that people and animals could breathe it. If only the carbon dioxide were reduced.”

“So have you made animal masks?”

They laughed and went up to the refuge commons, and Zeyk set about making coffee while they talked over the walk, and touched each other on the cheek to compare coldnesses.

“What about getting people out of the city?” Nadia said to Sax suddenly. “What if security keeps the gates closed?”

“Cut the tent,” he said. “We should anyway, to get people out faster. But I don’t think they’ll keep the gates closed.”

“They’re going out to the spaceport,” someone shouted from the comm room. “The security forces are taking the subway out to the spaceport. They’re abandoning ship, the bastards. And Michel says the train station— South Station has been wrecked!”

This caused a clamor. Through it Nadia said to Sax, “Let’s tell Hunt Mesa the plan, and get down there and meet the masks.”

Sax nodded.